Rice Production Takes Root in Maine

April 7, 2016 | Jennifer Osborn | (c) Ellsworth American

BLUE HILL — Rice production may bring thoughts of the Southern U.S. or the Far East reaches of the world, but homesteaders near Waterville are embarking on their third successful rice-growing season.

Ben Rooney and David Gulak founded Wild Folk Farm in Benton. They are developing an educational, research and experimental commercial rice operation.

“We just built a tiny little paddy and it did well,” said Rooney, whom the Blue Hill Co-op brought to speak at the Blue Hill Library March 31. The venture began in 2012 with five grains of rice seed from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

From there, the farm expanded its rice growing. This past year, Wild Folk harvested 400 pounds of rice. The farmers aim for a few thousand pounds in this upcoming season.

Homesteader and Wild Folk Farm co-owner Ben Rooney uses a hand-powered tool to remove the seed coating from the harvested rice.

The goal is to get as many farmers growing rice and Mainers eating rice as possible.

There aren’t any commercial rice growers in Maine and just a few homesteaders who are harvesting the crop. There are a few rice farms in other parts of New England — Massachusetts and Vermont.

“Most domestic rice farms in the United States are monocultures that rely heavily on fossil fuel driven mechanized cultivation and harvesting processes, and chemical sprays and fertilizers,” the farmers state on their website.

Wild Folk’s foray into rice growing developed in part from a trip to the Philippines, where Rooney was inspired by the International Rice Research Institute. It was also inspired by their farmland, which Rooney described as “pretty marginal soil” with heavy clay.

Rice growing can occur on wet farmland unsuitable for producing other foods.

“We’re not proponents of destroying your wetlands,” Rooney said. Prospective rice fields are probably not being used for anything else. Rice can be grown in marginal wet areas but not in areas so wet that cattails grow, he explained.

Rice yields twice as much per acre than any other grain and there are more varieties of rice than any other type of grain, said Rooney.

“We’ve been able to save our own seed,” Rooney said. “We can directly sow it and get a good yield.” By directly sowing, planters can create rice that’s well-tailored to their climates.

“You can develop a secure food system,” he said.

In a paddy system, the farmer controls the water and can grow other things, like watercress and water celery.

Another plus of the paddy system is that most weeds don’t like the water, Rooney said.

There are lots of frogs in the paddies but Wild Folk also keeps ducks, which churn up the soil in the paddy and help aerate it, which allows nutrients to be more effective and lower amounts to be used, he said.

If using ducks, you’ll want three to eight inches of water in the paddy. Wild Folk uses a spring-fed pond with underground piping to flow water into the paddies.

An outflow system is crucial.

“You’ve got to have somewhere for the water to go,” he said, especially if Maine gets a “crazy nor’easter” in the summer or in June when the rice is still short.

Someone asked about requirements of a pond for growing rice. Rooney estimated a quarter-acre-size pond for an acre rice paddy.

“If it’s in a low spot and it’s clay, you may not need a pond,” said Rooney.

Rice works well on a scale of 10, Rooney said. So one pound of rice seeds planted in a 1,000-square-foot area would ideally yield 100 pounds of rice.

This is the rice-growing season schedule:

April 10 – Germinate

April 20 – Sow in flats

May 20 – Transplant into paddies

Fall – Harvest

Rice can take a light frost but “it doesn’t love it,” Rooney said.

After harvesting, the rice is dried, threshed, hulled and winnowed.

Wild Folk uses scythes, sickles and human-powered equipment such as a foot-powered thresher.

Note — if anyone reading this has connections in Japan, the farm is looking for more foot-powered threshers.

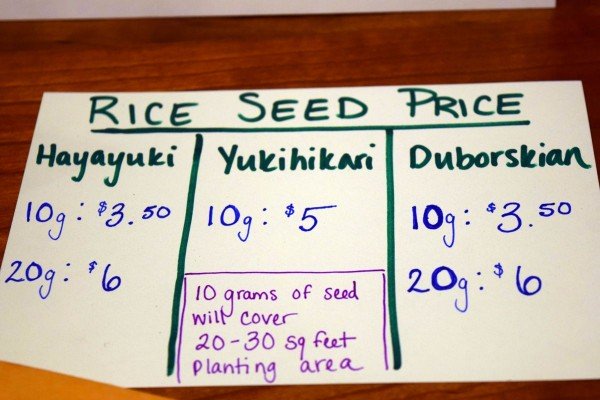

Wild Folk Farm is experimenting with varieties of rice but has successfully grown short, medium and long grain rice. They sell seeds as well as rice.

The varieties include yukihikari, which is described as the farm’s “highest yielding but latest maturing.” This variety can be grown in Zone 5b in paddy conditions or grown in Zone 5a or warmer in wet or dry conditions.

Hayayuki is the best variety for direct seeding in Zone 5 and can be grown in Zone 4.

Duborskian is a short grain, upland variety. It is the tallest, reaching 30 inches and maturing 115 days after transplanting in dry conditions or 105 in wet conditions.

Rooney said they are looking for seed companies interesting in selling their product.

The farm is also interested in letting others who grow rice borrow their equipment.